While reading Linda Villarosa’s New York Times article “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-death Crisis,” I had some visceral reactions as a soon-to-be mother. There are glaring and alarming disparities in maternal and infant health for women of color, particularly for African-American women like myself.

The article came to mind last month while I attended the 2018 CityMatCH Leadership & MCH Epidemiology conference, Partnering with Purpose: Data, Programs and Policies for Healthy Mothers, Children and Families. Health practitioners and researchers presented evidence-based public health programs and innovative strategies to promote and improve the health of women, children and families. They also shared ideas for how to advance racial equity in the health sector at a greater scale.

The article came to mind last month while I attended the 2018 CityMatCH Leadership & MCH Epidemiology conference, Partnering with Purpose: Data, Programs and Policies for Healthy Mothers, Children and Families. Health practitioners and researchers presented evidence-based public health programs and innovative strategies to promote and improve the health of women, children and families. They also shared ideas for how to advance racial equity in the health sector at a greater scale.

The problem

During each session at the conference, I found myself inundated and incensed by the same information in Villarosa’s article:

- “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notes that from 2011 to 2015, the percentage of women who initiated breastfeeding was 64.3 percent for African American, 81.5 percent for whites and 81.9 percent for Hispanics.”

- “Black infants in America are now more than twice as likely to die as white infants —11.3 per 1,000 black babies, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 white babies.”

- “Black women are three to four times as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as their white counterparts, according to the CDC.”

- “Education and income offer little protection. In fact, a Black woman with an advanced degree is more likely to lose her baby than a white woman with less than an eighth-grade education.”

Such health outcomes are frightening for Black mothers and their children, but the disparities also persist for other minority groups. For example, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, American Indian/Alaska Native mothers are 2.5 times as likely to receive late or no prenatal care as compared to non-Hispanic white mothers, and their babies are twice as likely as non-Hispanic white babies to die from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

Practitioners and researchers at the conference offered a long history of the debates over why such a minority-white divide exists in maternal health, infant birth weight, breastfeeding and mother/child mortality rates. The moral call to act — to engage those who experience the disparate outcome and cross-sector partners, to implement tiered systems-level interventions in the fight to eliminate racial disparities in maternal and infant health — was resounding.

Two key insights emerged for me during the conference:

Community-engaged partnerships are central to making a difference. Often initiatives to improve Native American maternal and children’s health (MCH) populations have only included the voice of health practitioners and health departments. Renee Lawson, pediatric clinic supervisor at Wind River Family Community Health Care Center, suggests addressing historical injustices and gaps in these populations. Tribes must be integrated into the U.S. public health system through effective partnerships with state health departments, community organizations and tribal-serving agencies. Using an inclusive collaborative model, partnerships among the Wind River Family and Community Health Care Center, Sage West and the Wyoming Department of Health led to changes to improve community infant mortality rates. One shift included client-centered reproductive health discussion in clinics. This approach focused on thinking about pregnancy planning and/or prevention based on client desires; respecting the ambivalence that Native women may experience when in contact with health professionals; and training providers on preconceptions about Native American health and patients as well as culturally respectful contraceptive counseling.

Community-engaged partnerships are central to making a difference. Often initiatives to improve Native American maternal and children’s health (MCH) populations have only included the voice of health practitioners and health departments. Renee Lawson, pediatric clinic supervisor at Wind River Family Community Health Care Center, suggests addressing historical injustices and gaps in these populations. Tribes must be integrated into the U.S. public health system through effective partnerships with state health departments, community organizations and tribal-serving agencies. Using an inclusive collaborative model, partnerships among the Wind River Family and Community Health Care Center, Sage West and the Wyoming Department of Health led to changes to improve community infant mortality rates. One shift included client-centered reproductive health discussion in clinics. This approach focused on thinking about pregnancy planning and/or prevention based on client desires; respecting the ambivalence that Native women may experience when in contact with health professionals; and training providers on preconceptions about Native American health and patients as well as culturally respectful contraceptive counseling.

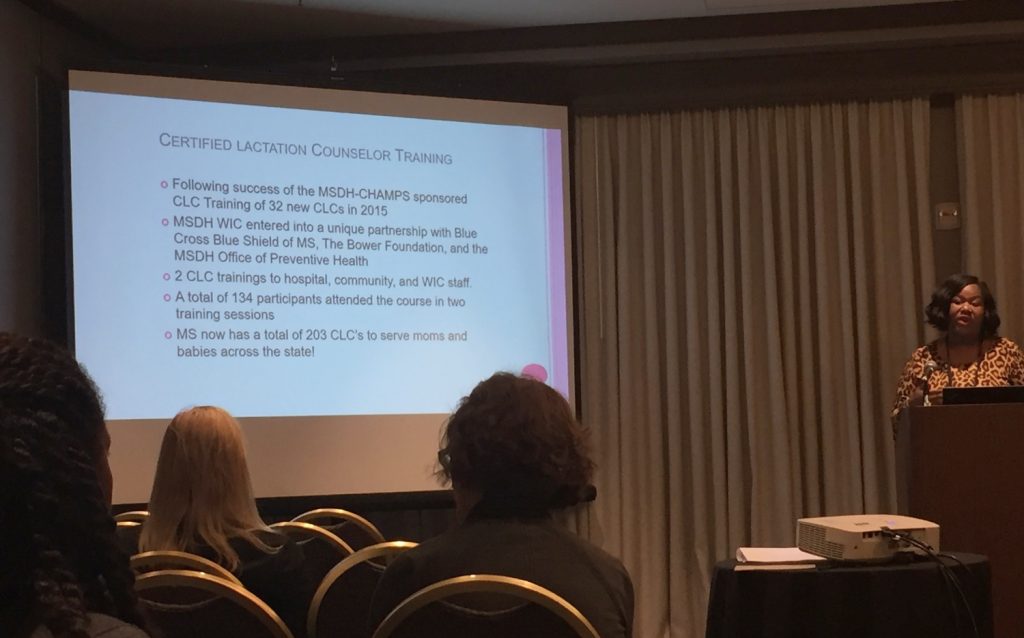

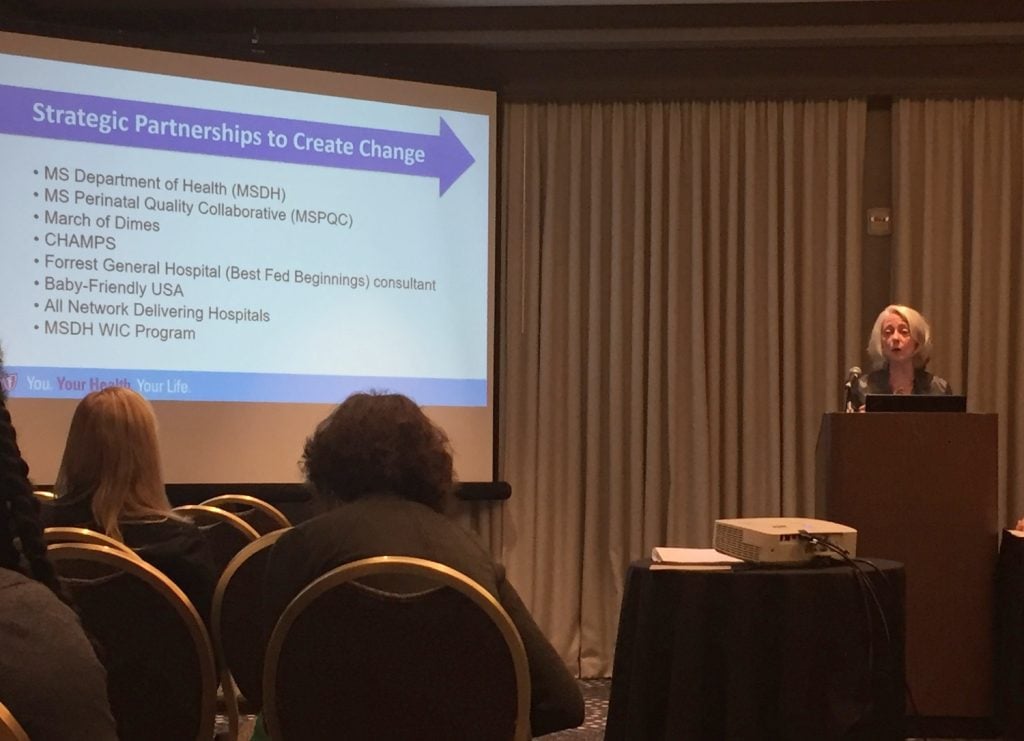

Gaps in health outcomes for mothers and children of color require interventions at various levels of the system. To be effective in this work, panelists at this year’s conference also encouraged every community to carry the right mix of practices, programs and policies at the state and local level to support vulnerable communities. For example, despite the many benefits of breastfeeding in maternal and child health, African-Americans mothers have the lowest rates. Some recommended solutions include increasing the number of hospitals becoming baby friendly with nearly all of the state’s hospitals entering the Baby Friendly Pathway; expanding the Baby Cafe community supporting breastfeeding practices; increasing health insurance coverage of breastfeeding resources; and transforming Women, Infant, and Children Food and Nutrition Services (WIC) programs from not only serving recipients to providing support to every woman through hospital and community partnerships. In Mississippi, connections among a host of different groups — the State Department of Health, the Mississippi Perinatal Quality Collaborative, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Mississippi, the Baby Cafe USA organization, statewide policymakers and mothers — have all contributed to this unprecedented change in the landscape of breastfeeding.

For any family supporting a woman who is carrying or having a child, it can be a turbulent and joyful journey. For women of color and their families, who face what could appear as insurmountable disparate outcomes in the maternal and child health space, the journey seems even more daunting.

Villarosa wrote in her article, “For Black women in America, an inescapable atmosphere of societal and systemic racism can create a kind of toxic physiological stress, resulting in conditions — including hypertension and pre-eclampsia — that lead directly to higher rates of infant and maternal death. And that societal racism is further expressed in a pervasive, longstanding racial bias in health care — including the dismissal of legitimate concerns and symptoms — that can help explain poor birth outcomes even in the case of Black women with the most advantages.”

Despite those seemingly intractable barriers, as an African-American woman and soon-to-be mother, I left the CityMatCH conference encouraged by the outrage of others in attendance. And in their outrage, they were collectively engaging and working at various levels of state and local health systems to improve outcomes for women who look like me and their children.