“Early morning, April four

Shot rings out in the Memphis sky

Free at last, they took your life

They could not take your pride”

“Pride (In the Name of Love)”

U2

This April 4, 2018, marks 50 years to the day the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Leaders across the country will reflect on his work, including “I Have A Dream,” “Letter From Birmingham Jail” and “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” his last speech. Along with Winston Churchill and John F. Kennedy, King ranks as one of the greatest orators of the 20th century. Five decades after his murder, we still look to him and his words to motivate us to fight for change.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others look on as President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

When we think about King’s work, we think about the marches, the organizing and the tireless work of him and thousands of others during the Civil Rights Movement and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The Civil Rights Movement resulted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 (passed by the House of Representatives six days after King’s death).

Often, we overlook the Poor People’s Campaign, King’s work at the time of his death. King and the Poor People’s Campaign advocated for changes that would prepare all people for the opportunities available from these legislative victories from the 1960s. The Campaign was a multi-ethnic effort for fairness and access to the American economic system for all people focused on race and income disparities. Essentially, it was equity work — the work of the entire StriveTogether Cradle to Career Network.

The Campaign also connected people through their shared struggle, bringing together a diverse group of people ranging from residents of Kentucky’s Appalachian Mountains to field workers from California. The Campaign’s first meeting included representation from more than 50 multicultural organizations. This approach is similar to StriveTogether’s model of Collaborative Action Networks, when cross-sector practitioners and individuals organize around a community-level outcome and use a continuous improvement process to improve that outcome.

Exactly one year before his assassination, King gave a speech in Chicago where he stated, “We as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. … We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society.” Since 1968, the gap between America’s wealthiest and poorest citizens has increased steadily. Using data from the IRS, economist Emmanuel Saez has shown that in a 20-year period from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s, the income gap increased 80 percent. Fifty years ago, King saw disparity gaps as a concern that should be addressed. Today, StriveTogether seeks to shrink this gap, with communities aligning resources to achieve better results for children.

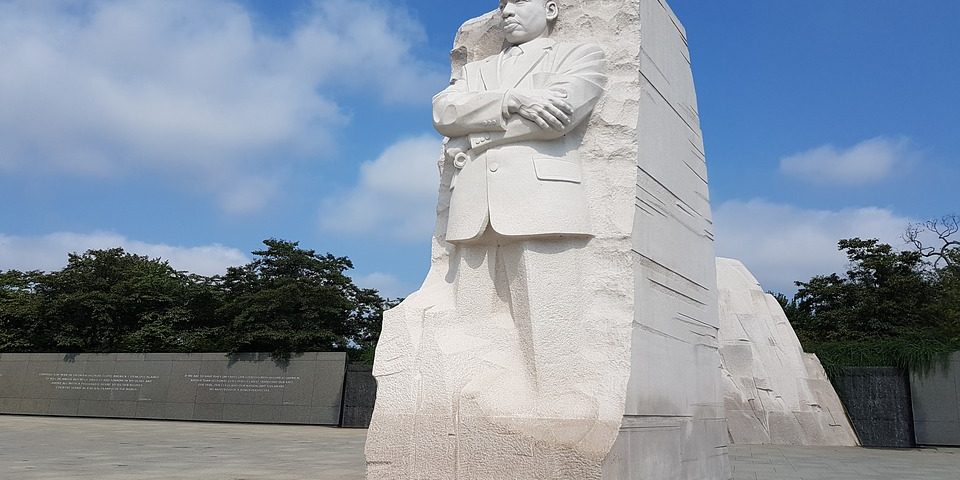

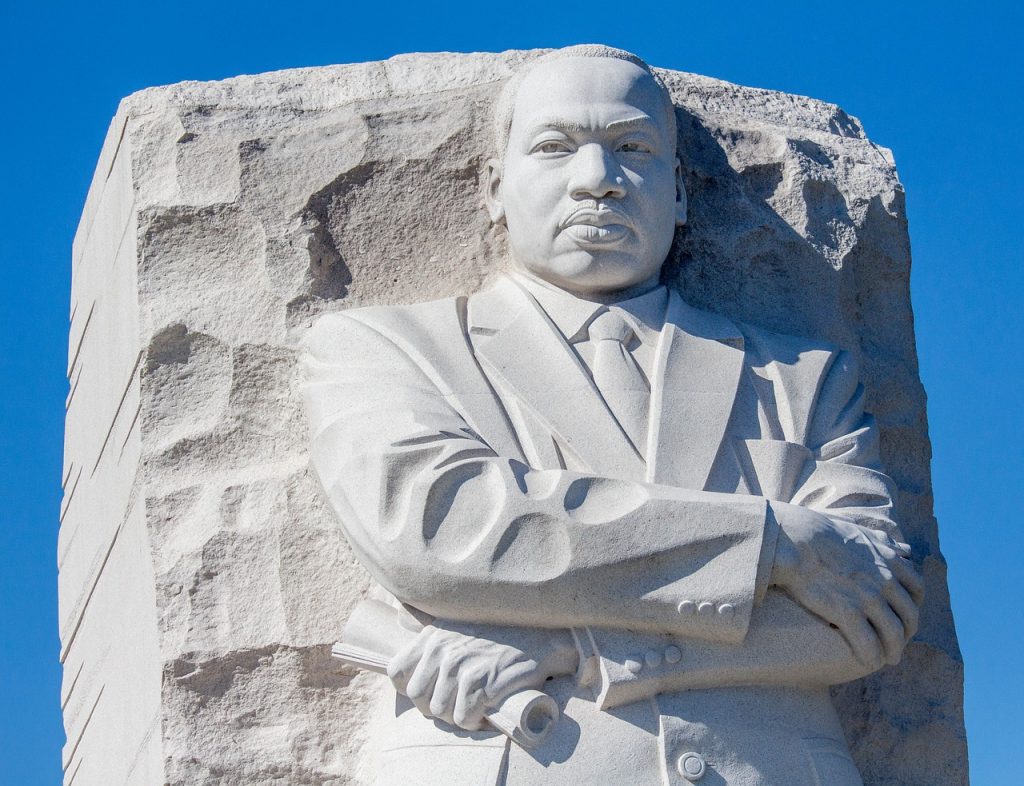

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C., features the Stone of Hope, a granite statue of King carved by sculptor Lei Yixin.

Although King’s work has at times been remembered as an individual achievement, it is an example of how to reach results through collaborative action and collective impact. For instance, the March on Washington could not have been accomplished without the Big Six. In the Big Six, King, chairman of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, worked with five leaders from other organizations. In addition to Rep. John Lewis from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, leaders came from the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the NAACP and the National Urban League. Two other leaders often are excluded when discussing the Bix Six (at times referred to as the Big Four): Dorothy L. Height of the National Council of Negro Women and James Farmer from the Congress of Racial Equality. The omissions of Height, a woman, and Farmer, a gay man, have been attributed to gender and sexual bias. An all-black collaborative but not monolithic, the Big Six was progressive, conservative, socialist, old, young, Christian and secular.

PolicyLink President Michael McAfee wrote in his paper The Soul of Collective Impact that “backbone organizations must have the courage, capacity, and credibility to take on the biggest problems in our nation, starting with structural racism.” McAfee also advocates for results-based accountability, a foundational skill that supports the Results Count™ approach. This approach includes using adaptive leadership, collaborating with others and highlighting and reducing disparities, while recognizing that race, class and culture impact outcomes and opportunities for vulnerable children. Decades after King mastered these skills, StriveTogether has staff trained in results-based leadership and provides offerings to the network to spread this approach throughout our communities.

As King’s work moved to the Poor People’s Campaign, his collaborative network expanded to a diverse membership in race, culture and economic status. It included Rodolfo Gonzales and Reies Tijerina, who informed collaboration on Chicano issues. King’s leadership and willingness to collaborate for results has been praised. As we reflect on his life, we cannot overlook his work to close gaps with a diverse group of people King and those working alongside him during the Campaign understood the importance of presenting disaggregated data, and the diversity of its leadership and sponsors (American Federation of Teachers, the YMCA and the United Steelworkers Union) reflected the population. In the StriveTogether network, disaggregating data by race is critical to supporting the success of every child.

In one of King’s last speeches during a visit to Mississippi in 1968, he spoke about the U.S. government excluding African Americans from land grants, which gave farmers property, tools and training. Following slavery and the oppressive practices of sharecropping in the Jim Crow south, farming was a trade in which many Blacks would have been successful. King presented this exclusion of Blacks as a case for the necessity of the Poor People’s Campaign and march. In this speech Rev. King would call out many of those beneficiaries of this federal subsidy. “Today these people are receiving millions of dollars not to farm and they are the very people telling the Black man that he needs to lift himself up by his own bootstraps. … This is what we are faced with and this is the reality,” King said in his speech. He followed that statement by saying the march on Washington was “to get our check,” meaning it was time for all people to be included in the economics of this country and the American Dream.

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech from this spot on the Lincoln Memorial steps.

Many other African American colleagues in the Cradle to Career Network and I are in the first generation of Black people to be born with our full rights as American citizens. There are many Black people we work with and respect in the Network who were not born with these rights. These rights were secured through the collaborative action and collective impact work of King, the rest of the Big Six and many others. It is safe to say King would expect collaborative work on behalf of today’s Dreamers, children who only know this country. He would expect us to work on behalf of Native American tribes that are recognized as sovereign nations but face mass incarceration in a U.S. justice system that operates outside of the cultural norms of each of these nations.

On April 4, let’s ask ourselves and each other if we are keepers of the dream. The dream, as presented on August 28, 1963, during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, did not stop that day. It grew into collaborative work for improving conditions of all people, specific to the issues of every racial group and culture with respect to geographic areas. StriveTogether’s new strategic plan speaks to the equitable outcomes King sought when he died. As a network, we collectively are all keepers of the dream and the work of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. is our work.