Last month, the Spartanburg City Council unanimously approved a resolution to acknowledge systematic racism and apologize to Black community members for the persistent inequities caused by past city policies.

Last month, the Spartanburg City Council unanimously approved a resolution to acknowledge systematic racism and apologize to Black community members for the persistent inequities caused by past city policies.

The resolution was led by councilmember Meghan Smith, who serves as director of college/career readiness at Cradle to Career Network member Spartanburg Academic Movement (SAM). We connected with Meghan to learn about the process and hear her advice for other communities who would like to take a similar step.

Where did this process start for you?

Back in May, someone sent me an article about how Franklin County, Ohio, had passed a resolution declaring racism a public health threat. After George Floyd was killed, our city reacted quickly to bring members of the community together. And that was what kicked up my interest to try to get something like this passed, something really unambiguous as to where we stood. I did a lot of research on what other communities had been doing and saying and then began to work with our staff and other advocacy groups here in Spartanburg to develop our own version.

Who did you need to work with to make this happen, and what did it look like to get them on board?

The group I was focused on the most were my other council members. Discussing race, systemic racism and how to move forward are hard conversations to have. There was some initial concern about the apology. “How can we as current individuals apologize for anything in the past that we personally weren’t a part of?” It took shifting the conversation from thinking of an apology as responsibility more to empathy. “Yes, I, as Meghan Smith, was not alive even in the 70s during urban renewal. But as a voice for the city, I can express to you that I am sorry for what happened to your community.”

And then there was some concern initially about using the word racism. We are fortunate in Spartanburg — and I think SAM is a big part of it — in that we have a lot of data related to different outcomes and disaggregated data. There was some initial discussion of just denouncing racial inequities. I was pretty adamant about the fact that those inequities exist because of racism. If we can’t name something at the core, we don’t need to be in the business of talking about this at all.

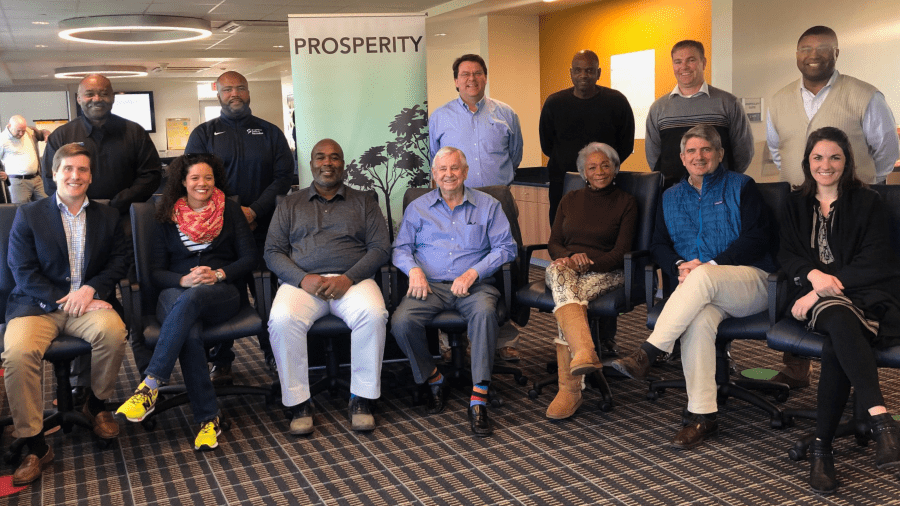

Spartanburg city council members participated in a retreat facilitated by Dr. Russell Booker, current executive director of Spartanburg Academic Movement and a member of the StriveTogether board of directors.

What feedback have you gotten since the resolution passed? What have you heard from community members?

What I’ve heard is that it has meant different things depending on your age. One conversation that was highlighted through this process was Spartanburg’s history of urban renewal, the time in the 1970s when cities were given federal funds for new infrastructure. A lot of times that infrastructure was put in the Black community at the detriment and destruction of current neighborhoods.

During the citizen comment time, people would come and talk about how the street that they grew up on doesn’t exist anymore, or their doctor’s office was destroyed in the 70s. For some of those people who lived through that time to hear that part of their own history recognized, I have heard, was a very validating experience.

For younger people who weren’t alive then but experience systemic racism in different ways, I think it felt validating to them in the sense that their advocacy actually had a result. That process invited new people in who hadn’t been involved in any government process like that before.

This work is about Spartanburg’s history, but what impact do you see it having on future generations? How do you think it will make a difference for kids to grow up in an environment where generational trauma and institutionalized racism are recognized?

In the past, kids in Spartanburg grew up with a city government that actively promoted segregation in schools. Now, they’re growing up under a city government that has said, “We’re sorry.” What trickles down from that is the investments that we have made back into the communities that were destroyed during urban renewal.

I believe that this resolution is one small piece of a culture shift. I think people’s values and mindsets and ideals are born out of their culture. We know from the work we do through StriveTogether that we’re talking about generational change. This is just one building block toward a culture in Spartanburg that truly values every single life and works equitably to create opportunities for all of those lives.

Spartanburg city council member Meghan Smith is sworn in.

If someone would like to pass a resolution like this one in their own community, where should they start?

Each community is so unique, and the starting point for each place is going to be so different. Data is a great place to start. It’s important to understand where the disparities are in your community. Find those who work in that field — whether that’s education, or health, or business — and gauge their support. Making relationships with your city council and the staff is really important, too.

Then you get into advocacy 101. Do you do an email writing campaign, do you reach out to local media and have a story told about what you’re trying to do and what the history of your area is? Understanding that history is an important first step as well. People say, “What are we apologizing for?” I ended up preparing a document to give to people when they said that.

Knowing your data, knowing your history and knowing the players — those that hold the power for something like this — are three places I would tell people to start.

What would you say to someone who wants to lead a similar initiative but worries they’ll face a lot of resistance?

Expecting resistance is important, even just for your own expectations. When you expect resistance, it stokes something in you to be all the more prepared. It sounds like a cliché, but there is power in numbers, so shoring up your allies in the work is really important both for getting something accomplished and for your own mental health. If you try to do anything in racial equity alone, it’s not going to be a fun journey.

Expect resistance but keep pushing. A friend of mine kept saying, “Be on the right side of history.” Those people that we consider now to be on the right side of history were the ones that got resistance. And they faced it far worse than we ever will as white people right now. There’s kind of a check that happens with your own privilege. What is the resistance I receive compared to others who came before me to prepare this moment? That perspective can lead to gratitude and help you stay in the fight.

Meghan and a coworker from Spartanburg Academic Movement pose the 2018 Cradle to Career Network Convening in Seattle, Wash.

What’s next for Spartanburg? What’s your hope for what this resolution will make possible?

My goal is that it will hold us and future councils accountable to this work. And that our city staff can use it in determining their budgets. And as new developers come into town and want tax incentives from us, we can say, “We have a council that really values racial equity. And for you to get support from the city, we’re going to need to see this much affordable housing included in your development agreement.”

We’ve declared what our values are, and the work will come behind it. And for some of the work that will be controversial, we can say, “We’ve already committed to this, and we committed unanimously. And so we’re just following through on what we’ve promised to do.”

I want to move forward in a way that is very collaborative and ultimately creates systems change. We can do one-off programs here and there, but those are all just going to be Band-Aids unless we really change the whole system for better outcomes.

Ultimately, I hope it has grown the table for new voices and people to feel included in their city government and that they’ll keep paying attention and holding us accountable to this work. We are accountable to our voters, and having more people pay attention and be civically engaged has always been a North Star for me personally. One of the greatest joys has been for people to express that this has been an invitation to participate in a process that they didn’t feel included in before.

Meghan Smith is director of college/career readiness at Spartanburg Academic Movement. She began her first term on the Spartanburg City Council in January 2020.