In 2013, 50 public schools closed in Chicago — the largest mass public school closure in the history of the United States. Of the 10,400 students affected, 88% were African American.

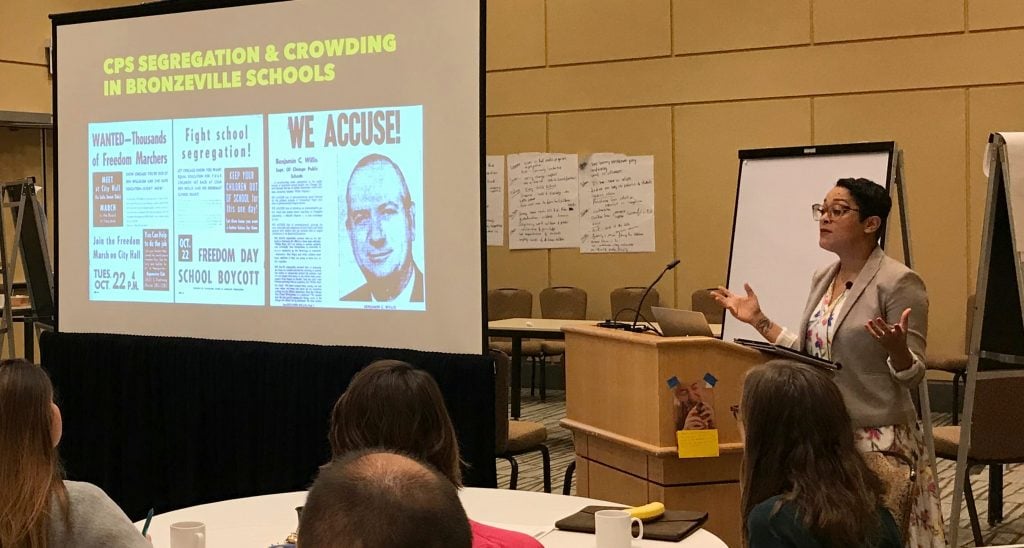

Last week, sociologist of education Eve L. Ewing shared insights from this event with Cradle to Career Network members gathered to deepen their work at StriveTogether’s Racial Equity and Inclusion Convening: Moving from Talk to Action. Highlighting lessons from her book “Ghosts in the Schoolyard,” Eve explored the cause of the school closures and their disproportionate effect on black communities.

“I don’t see this as a story about one city or about school closures in particular,” Eve said. Rather, she said, she looks to the event to learn “how we can be more honest about our history in order to make more equitable choices as teachers, school leaders, community members and policy makers.”

Here are three key insights from her talk:

The systems that shape opportunities for kids and families intersect and problems compound each other, so solutions must take a cross-sector view. The story of the school closings, Eve shared, shows the interdependence of housing, education and other sectors that affect families.

Chicago’s African American population grew rapidly during the Great Migration that followed World War I. The city’s new black residents settled in a restricted geographic area, prevented from moving elsewhere by real estate laws and violence. As more families and children arrived in the neighborhood, called Bronzeville, a housing shortage quickly appeared.

Faced with violent resistance to integrating housing throughout Chicago, the city filled Bronzeville with highly concentrated, high-rise public housing. As population density increased, schools in Bronzeville became more and more crowded. Over the next few decades, segregation and the community’s lack of resources worsened.

In 1999, responding to the declining perception of public housing, Mayor Richard M. Daley announced a plan to demolish all of Chicago’s high-rise public housing. With this sharp decline in the neighborhood’s population, the schools that had once been overcrowded were now emptying, leading to what school officials called underutilization.

“The history of segregation, even when it seems very distant, actually does a lot to shape our present moment and our present reality.” — Eve L. Ewing |

Our history continues to shape our present, and this context must be addressed in making policy decisions that best support every child, regardless of race, zip code or circumstance.

While underutilization was the most widely cited reason for the 2013 school closings, Eve said, this reasoning was conspicuously missing discussions of the roles of segregation, history or housing.

“The history of segregation, even when it seems very distant, actually does a lot to shape our present moment and our present reality,” she said.

Eve shared that she’s often asked a seemingly obvious question: “Are school closings always bad?” No, she answers, we need to adapt to new circumstances to best serve students. But history and context matter. And in the case of the 2013 Chicago school closures, a 2018 study by the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research revealed that the decision failed to help students.

This story doesn’t end in Chicago or in 2013, Eve said.

“We have to look forward to the recurrence of not only this policy question — should we close schools? — but any policy question, whether it’s at the classroom level or at the district level or at the state level, that runs the risk of disproportionately harming communities that have already been disrespected, disregarded and marginalized,” she said.

“We have to look forward to the recurrence of not only this policy question — should we close schools? — but any policy question, whether it’s at the classroom level or at the district level or at the state level, that runs the risk of disproportionately harming communities that have already been disrespected, disregarded and marginalized,” she said.

Changing adult behavior changes systems. To avoid repeating harms, communities need to think critically about such decisions and frame them in historical and social settings, “even when that means facing some very ugly history,” Eve said. Despite the discouraging patterns of the past, she sees reason to have hope for the future.

“Human people made these decisions through human polices, and what that means is that human people can unmake them,” she said.

To learn more about Eve’s work, connect with her on Twitter and visit her website.