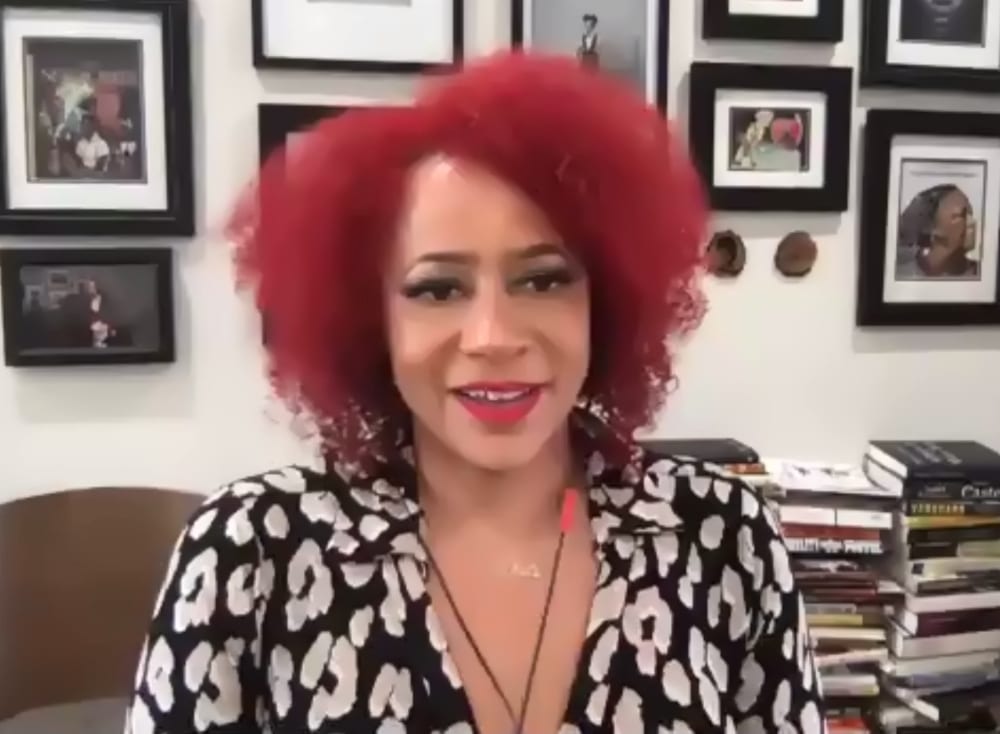

Nikole Hannah-Jones ended the 2020 Cradle to Career Network Convening with a powerful message for the audience of more than 1,400 community changemakers: Keep pushing and bring along allies to reconstruct the architecture of racial apartheid.

Hannah-Jones is the Pulitzer Prize-winning creator of the New York Times Magazine’s “The 1619 Project,” which shares the history and lasting legacy of American slavery. The Root named that she “is changing how history is taught, and this year, after helping to reignite the discussion about reparations and racial justice for Black Americans, she’s reframing what the future looks like, too.”

And for this year’s convening attendees, Hannah-Jones did just that — offering a reframe of how to fix systems that have disproportionately impacted Black Americans. First, she encouraged changemakers to know their history.

“You cannot fix systems if you don’t understand how they were architected in the first place,” Hannah-Jones said. “You can’t just ignore some of the past simply because it was uncomfortable.” The romanticized, patriotic history prevalent across our education system has downplayed the anti-Blackness, racial apartheid and racial terror experienced by Black Americans. This leaves many of us, including students, without the shared language to talk why we have gotten to where we are related to race.

She encouraged folks to study the history, look at the data and “draw the very direct lines between what occurred in the past and what happens now.” And acknowledge what some are afraid to name — that yes, white people have worked hard, but they have worked hard in a system that was designed for them, and Black people have worked hard, too.

“No one worked harder than somebody who was enslaved, and yet they were working in a country where they were not the beneficiaries of that labor,” Hannah-Jones said.

Drawing on her work in “The 1619 Project,” Hannah-Jones explained that the disparities Black Americans face across outcomes — health, education, wealth and more — are driven by the 350-year financial head start given to white Americans, along with “centuries of policies that have benefitted white Americans.”

Drawing on her work in “The 1619 Project,” Hannah-Jones explained that the disparities Black Americans face across outcomes — health, education, wealth and more — are driven by the 350-year financial head start given to white Americans, along with “centuries of policies that have benefitted white Americans.”

And while Black Americans may have civil rights on paper, those rights are not always a reality. Alluding to the Breonna Taylor verdict, Hannah-Jones said, “Black Lives Matter less than the property of white people.”

Through the lens of history, Hannah-Jones drives home this point — there is a large disconnect between our espoused values as a nation and the reality that exists for communities of color.

“The same cities painting #BlackLivesMatter in the streets have still not passed criminal justice reform,” Hannah-Jones stated.

Her home of Brooklyn, New York, is in a blue state, she shared, but it’s among the most segregated cities in the country in housing and schools. “You have white Brooklynites who would put a Black Lives Matter sign in their yard, but they are not going to send their kids to school with the majority of the children they say they’re marching for,” she said.

And while there is an appreciation for social media activism and symbolic changes, like tearing down Confederate statues, Hannah-Jones asks, “When will we actually see the real, structural changes?”

She challenged this year’s changemakers to face the reality of our history and our current inequities: “If we are truly a courageous country, we must bear the truth of our failures.”

Acknowledging that she is a journalist and not a community organizer, Hannah-Jones offered up the following ways to acknowledge those failures and move equity from a buzzword to an action:

- Talk to your school board and tell them to teach our real history.

- Support public education.

- Stop funding schools through property taxes, which exacerbates inequities.

- Collapse schools so real estate is not being used as a way to segregate schools.

And while these suggestions are possible, Hannah Jones wearily noted the lack of political will to move some of these things forward. As explored in the podcast Nice White Parents, white parents wield an inordinate amount of power within schools. Because of this, school districts and school leaders are beholden to them and — out of fear of losing middle-class parents in their district — too often don’t advocate for what’s best for all students. Hannah-Jones’ message for those parents? “Start wielding that power not just for the benefit of [your] own kids and kids who look like [your] kids, but for the benefit of all children.”

Hannah-Jones shared messages for all changemakers, both those most impacted by disparities and their allies.

Messages for allies

“It’s not whether you are a good person or not. Are you using the values that you espouse?”

“The hard decisions [around equality and justice] require us to do something different for our life.”

“It’s far different to say, ‘I’m moving into this neighborhood where I am driving up property values. Should I do that?’”

Messages for people of color

“From the moment we landed on the shore, we have fought, and while other people can grow tired and move on, [Black Americans] don’t have that choice. We have to keep pushing even as our allies leave.”

In continuing the fight, she encouraged Black and Brown people to resist the narrative that success means getting an education and leaving the neighborhood, but rather to stay in their communities and invest. And while others might give up the work of creating equitable systems, we must use our “tremendous power to fight for our kids.”

Akia S. Callum, Waterbury Bridge to Success Partnership

Our conversation with Hannah-Jones was facilitated by Akia S. Callum, director of community impact and marketing for Waterbury Bridge to Success Community Partnership. Callum’s work to center youth voices is rooted in the need to understand the history of her community as they uplift intergenerational leaders.

I’m leaving the convening energized to understand more deeply the history of my own community in my work toward systemic change. I am encouraged because I know that changemakers like Callum are answering Hannah-Jones’ call: to investigate the root causes of disparities so that we can reframe our approach to transforming the systems that have disproportionately impacted Black Americans.