we constantly

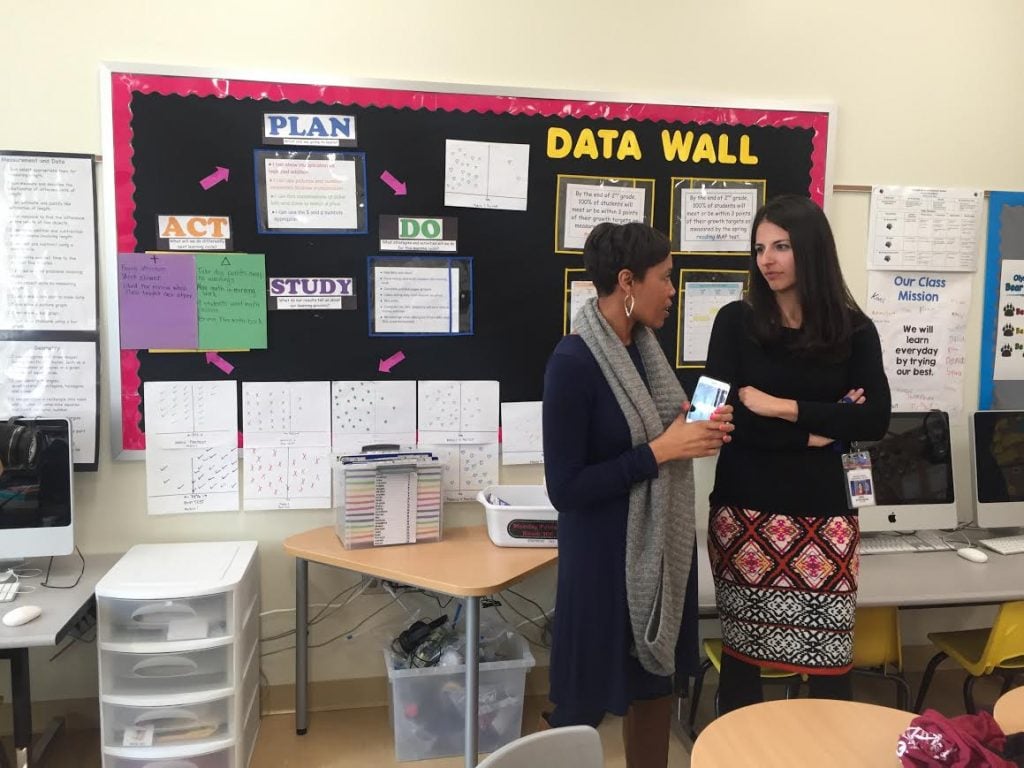

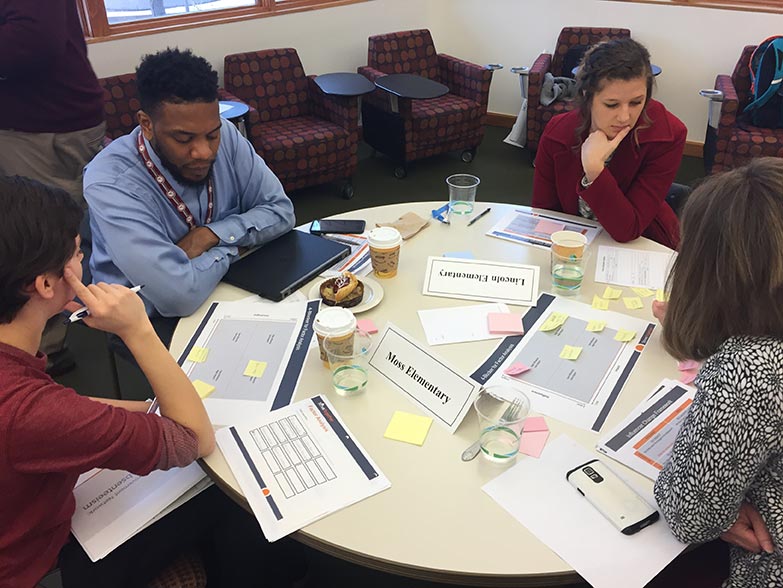

At StriveTogether, success is shaped by learnings from our communities.

insights

shared wisdom

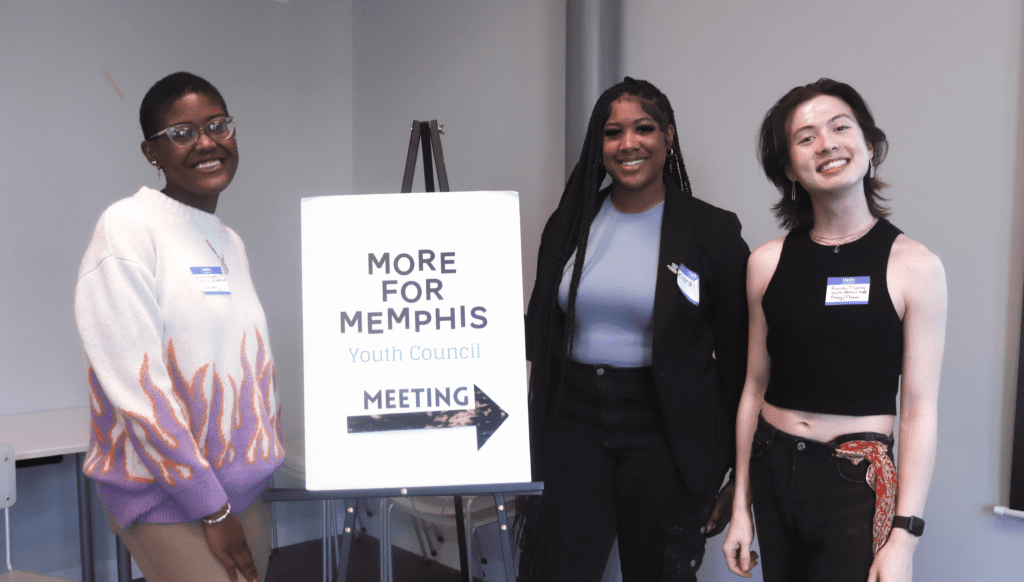

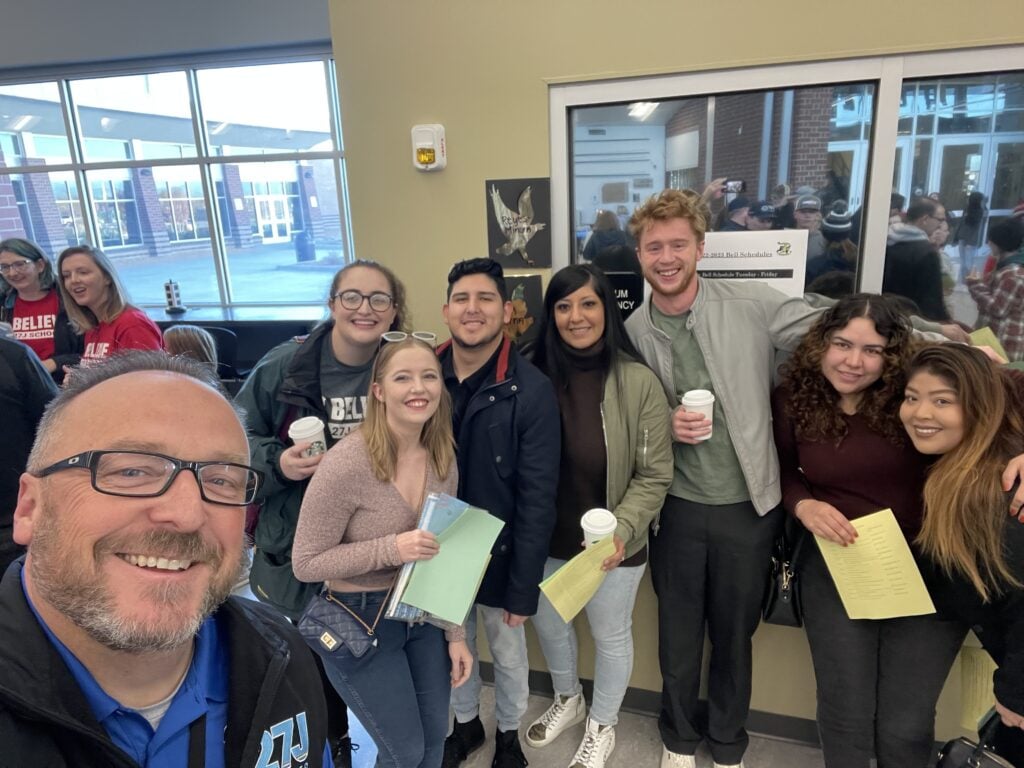

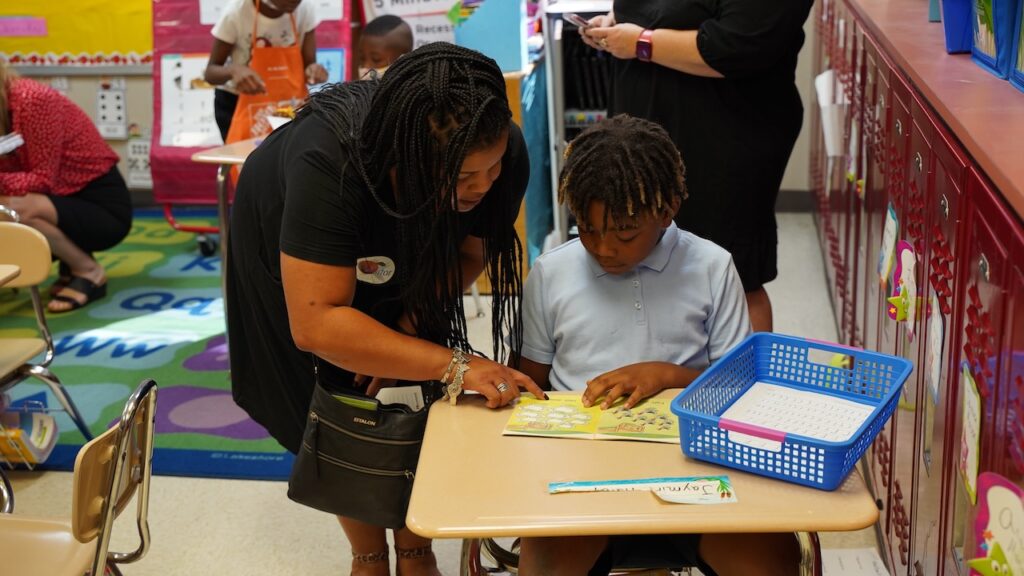

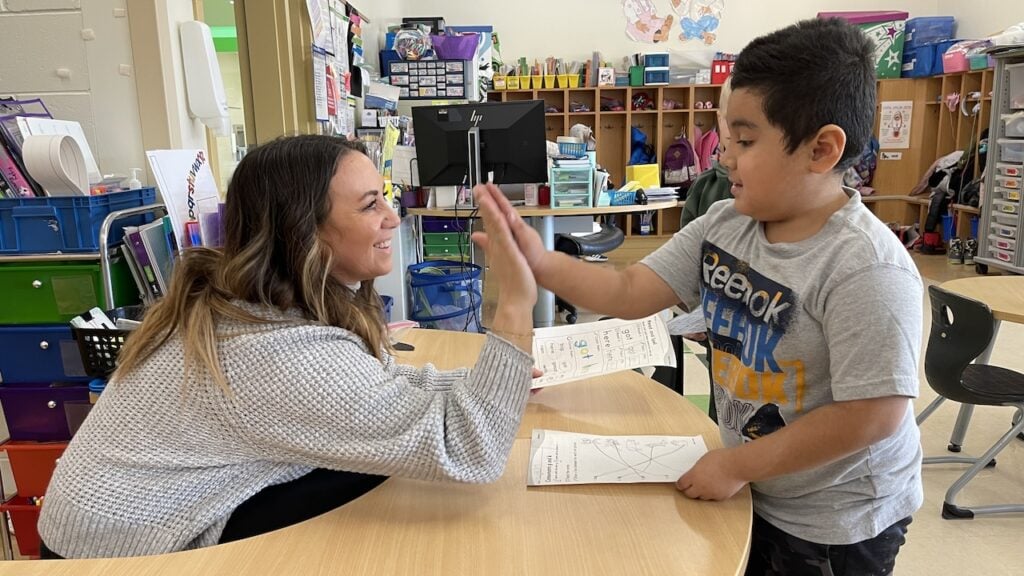

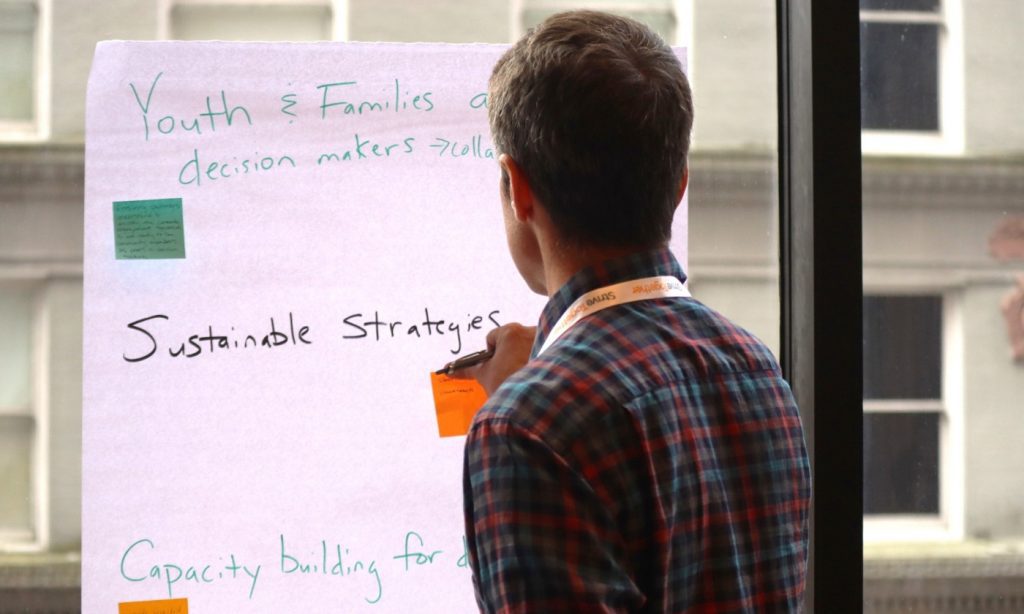

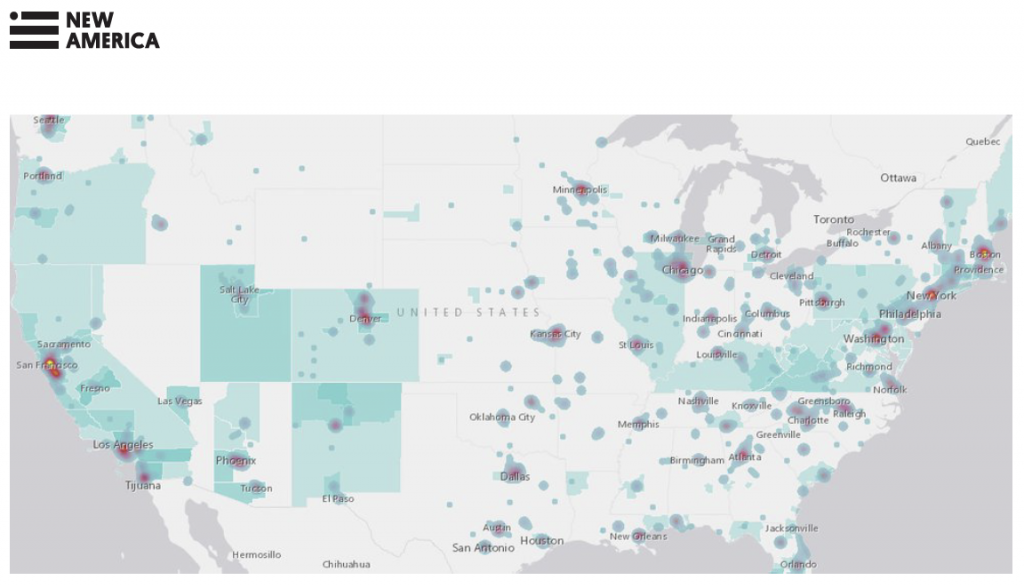

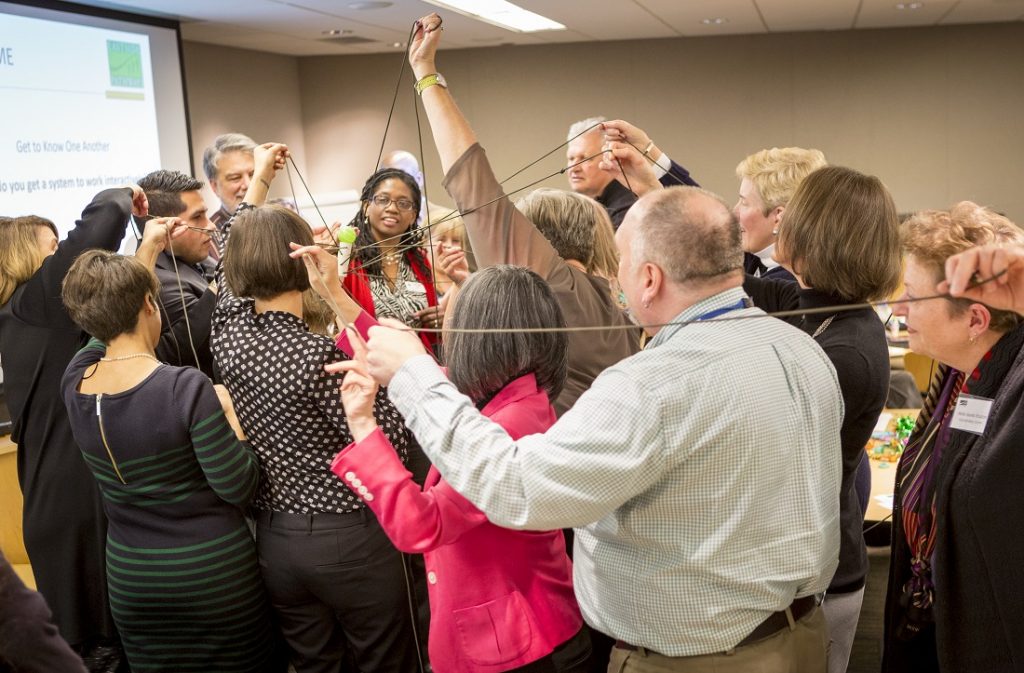

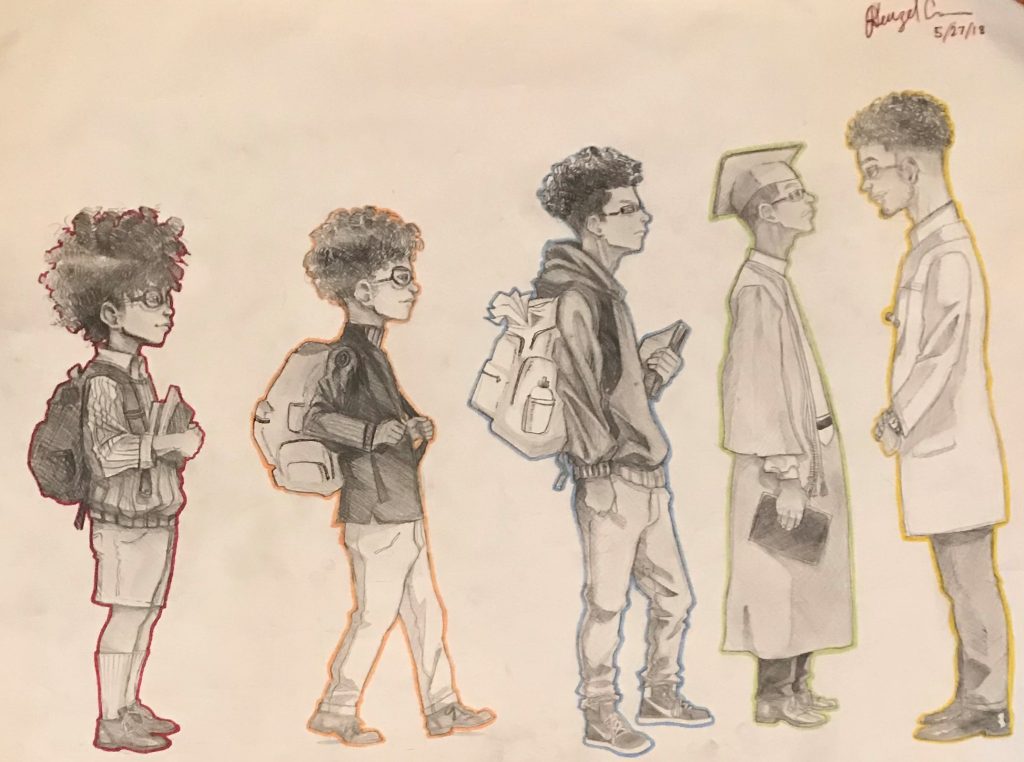

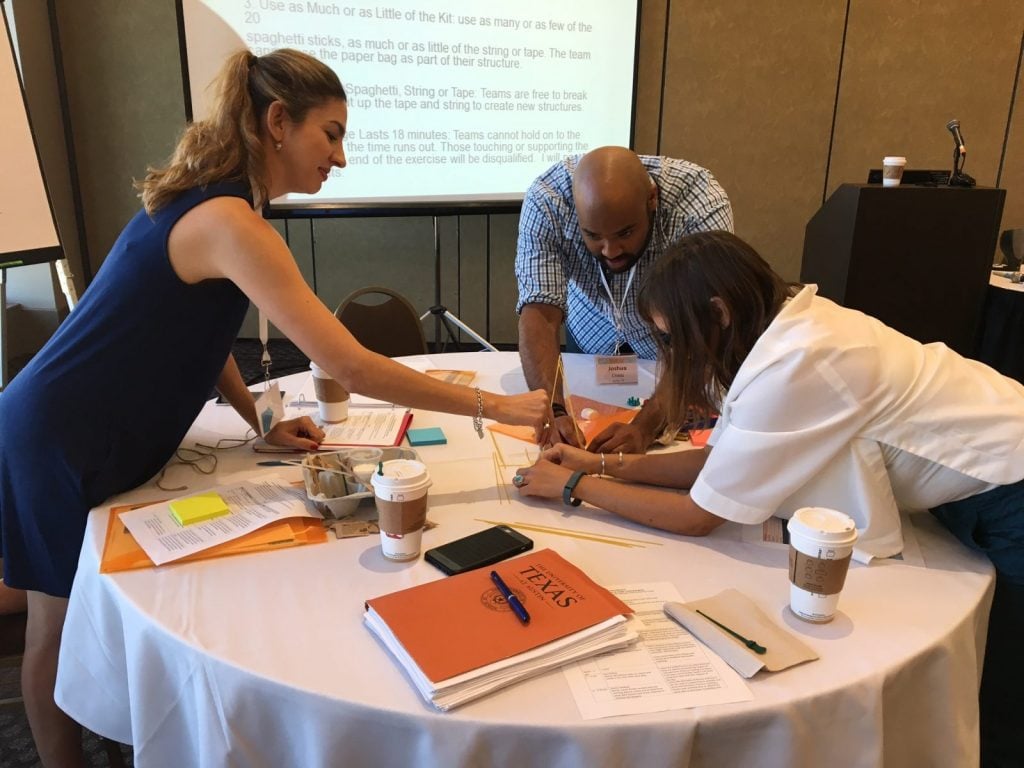

Peer-to-peer learning powers our Cradle to Career Network and generates lasting impact in StriveTogether communities. Here, you’ll learn about the latest and most innovative work transforming the systems that serve youth and families and find new strategies to accelerate your own results.